Why your career satisfaction is a big deal

It’s a privilege to choose your career. But that shouldn’t stop you from choosing one that actually makes you happy. In fact, it’s better for the world if you do.

Thriving in any pursuit is often the result of finding a paradoxical sweet spot between caring very much and caring very little. Caring very much means that you’re willing to put all your energy, drive and passion into creating something or making something work. Caring very little means that you’re okay with this thing crashing and burning without being too badly affected.

Putting all your drive and passion into something is an energising experience. Have you ever experienced it? Are you currently experiencing it?

Or, are you being drained by your work, spending hours scrolling other jobs on LinkedIn or spending most of your working hours planning a getaway for the summer? This might be a sign that you’ve gone too far into the “caring very little” end of the spectrum. Basically, you’ve lost hope about things improving with your career. Some call this quiet quitting.

Maybe you’re having thoughts like:

Well, maybe I’ll just invest in my free time.

I do have these great benefits at my work so there’s no point leaving. And the economy is bad anyway.

None of my friends is happy with their work either so I’m not sure career satisfaction is even possible.

My colleagues are still nice.

And, if you come from a privileged background, you’re likely told to respect what you have and not get too carried away with your ambitions.

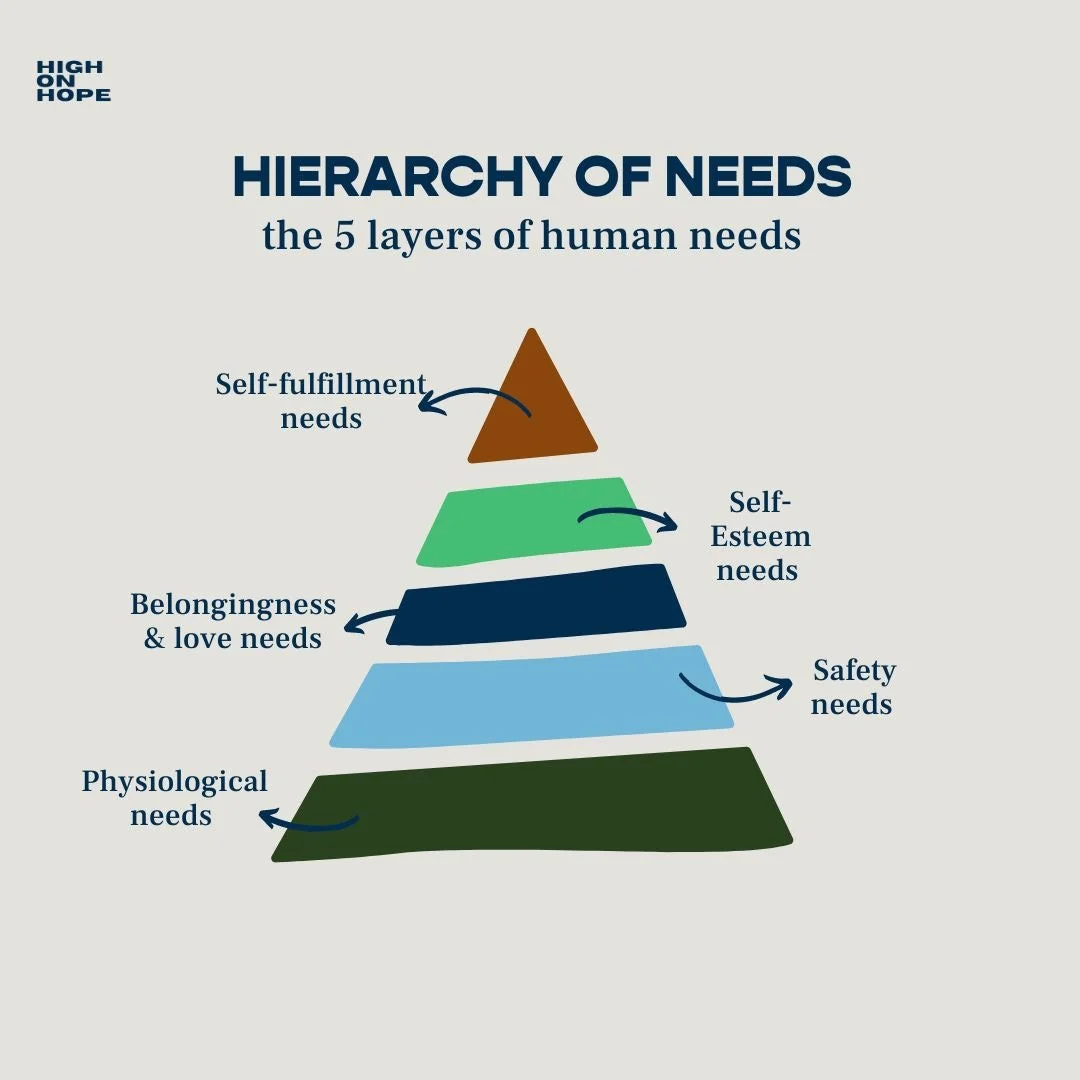

From a Maslow’s hierarchy of needs perspective, you’re at the very top. Because you already have the lower levels of the hierarchy covered, such as food and shelter, employment, friends and some achievements under your belt, you can spend your time exploring your sense of purpose, meaning and inner potential. Topics that boomers often classify as a bit “woo-woo”.

Because we don’t spend our lives figuring out how to survive literally, Gen-Y and Gen-Z representatives ask different kinds of questions than our grandparents and parents. We ask, whether we should be working so hard, whether capitalist values can be sustainable, and whether we should have some type of purpose in our careers instead of just working for a paycheck.

We ask: Should we actually believe in what we do 40+ hours a week?

I believe there are two sides to every story. I’d agree that some Gen-Y and Gen-Z career dissatisfaction comes from having too many choices and being bombarded with success stories that make everything look far too easy. Many people step into working life thinking that success should happen overnight. Some may believe that you should never struggle, feel overwhelmed or work hard to achieve something.

The other side of the story is that our economies have reached a state where profit maximisation and efficiency have surpassed enjoyment, purpose, human thriving and planetary boundaries. Instead of enhancing our societies, we’re enhancing profit margins.

And that’s where millennial and Gen-Z resistance becomes less of a personal story but a societal story.

Your career isn’t irrelevant or merely a private affair

In Europe, several countries struggle with mental-health-related absence from work. In Germany, a new record for these types of absences was reached in 2021, a number that went up by 41% from the previous year. Also, an average sick leave for mental health reasons lasted for as long as 39.2 days. In Finland, anxiety-based mental health issues are now the most concerning trend for absences, affecting especially under 35-year-olds.

A report created by Microsoft and LinkedIn called the Work Trend Index 2024 says that 68% of individuals report difficulty coping with the speed and workload, while 46% experience burnout. According to the same study, 46% also consider quitting their jobs in the year ahead.

The OECD has stated: The costs of poor mental health are high: the total cost of mental illness is estimated at around 3.5% of GDP. People with mild to moderate mental illness, such as anxiety or depression, are twice as likely to be unemployed. They also run a much higher risk of living in poverty and social marginalisation.

Our careers matter. Every sick leave, every failed recruitment, every onboarding process is worth something – not just symbolically but in real-time cash, cash, money, money.

Someone is paying for your dissatisfaction.

So if you think your career confusion is just your personal problem, you’re wrong. If your career is making you sick or unmotivated, it becomes a societal problem.

That’s why I don’t think we should think about our careers lightly or be quieted by the narrative of “spoiled zoomers.”

Instead, we should try to look for something that aligns with the worldview we hold, even when it’s different from our grandparents.

In fact, I think we need to stop the comparison game between the work-life of 2020s and the 1950s. Yes, people had different ambitions and values because everything was different! The population was smaller, careers were longer, and communities were stronger.

So why bother getting stuck in comparison? Our grandparents aren’t here to do the work anymore, are they?

They’re neither here to get screwed over by the gig economy nor to save the world’s oceans from reaching a detrimental temperature.

If we want to create meaningful change in this world, we need to focus on the people we are now.

Ask for the things that matter to us. And change the world by doing so.

How can we start to care very much?

So, let’s go back to that paradoxical equation of caring very much and caring very little.

We need to put more emphasis on the “caring very much” end of the spectrum. We need to find careers that light us up and energise us to do the hard things involved in any vocation.

Now, I want to make it clear that I don’t mean just a career that you care about or that sounds meaningful. I’ve met many people in important jobs, such as nursing, who feel a deep calling to do the work they do, but they’re miserable. Their misery comes from the fact that they’re understaffed, disempowered, and treated awfully by their bosses. Some of them are burning out and some are quietly quitting even though they love their actual work.

Now, this is not sustainable.

A career that lights you up is not just about the why behind your job but it’s also about the what and the how. Sometimes, how you do your job is more important (or at least equally so) than the why. If the leadership sucks, you never get feedback and you’re always expected to do three people’s jobs, it’s hard to feel like you have much to give even if the why is aligned with your values.

As such, not all career changes need to be dramatic. Sometimes it’s enough to change the hows instead of studying for years to create a completely different career. For example, a nurse might start their own healthcare company to create the type of leadership they want to see in this world.

The world does not need more burnt-out or unmotivated people. It needs people who actually want to work, create impact, and yes – pay taxes.

This is why I do what I do. I want to improve work-life one career at a time. I want to help people get lit up without burning out. I want to support people in finding that sweet spot between caring very much and caring very little. This gives me a sense of purpose even though someone might consider it miniscule.

But I believe in the power of people.

I believe that our investment in our careers creates good in this world. When you are energised by what you do, you become a source of energy for others. You’ll have the type of hopefulness that the world needs right now. Your choices contribute to the larger narrative of what work-life should be.

You might think your choices are trivial but they’re not. Every single one of us has a role to play in creating the future we want to live in.